Improving New Jersey’s CSO Strategy

March 24, 2021Combined Sewer Overflows (CSOs) are a significant environmental problem in New Jersey, resulting in billions of gallons of sewage entering the state’s waterways every year. Current approaches to solving the problem have made some progress, but the policies in place achieve only partial solutions at a snail’s pace. In order to eliminate CSOs and do so faster, funding for the state Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) must be increased through the reallocation of state finances and the establishment of new taxes.

What are CSOs?

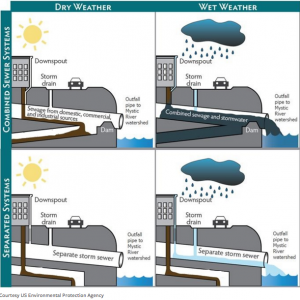

Combined Sewer Overflows, also known as CSOs, are sewer systems that are connected to a city’s stormwater management system as well. In a CSO system, any stormwater that is collected will join municipal sewage in its path to a sewage treatment plant. An advantage of CSOs is that sewage and stormwater management can be coupled, thus making things convenient for municipalities.

However, the downside of CSOs is that if it rains heavily, so much stormwater can merge with sewage that the sewage treatment plant cannot treat all of the waste it is receiving quickly enough. This can result in some sewage-stormwater mix emptying into local waterways, as shown in the figure below.

FIGURE 1: Combined Sewer Overflows (Top) Compared With Separated Sewage-Stormwater Systems (Bottom) (Image Source: NY/NJ Baykeeper)

The sewage that enters into local waterways from CSOs can contaminate local waterways and become a public health hazard. This sewage also prevents recreational activities from taking place on affected waterways, and from an economic standpoint, sewage-contaminated waterways cannot be exploited for fishing or oyster production.

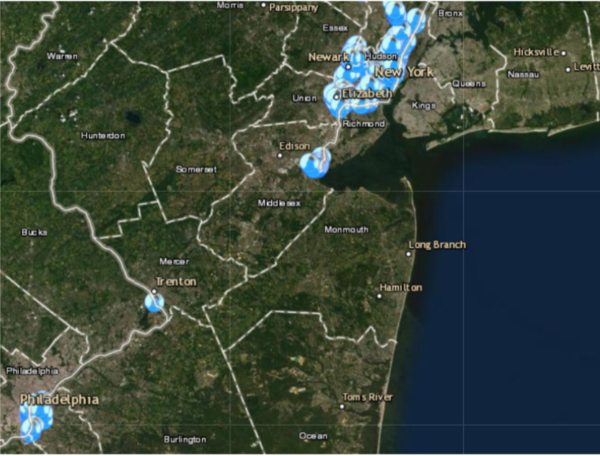

Due to CSOs harmful effects, they have been mostly phased out of development today, and they are now remnants of this country’s early urbanization. Unfortunately, many CSOs are still present across the country and especially in New Jersey, as many municipalities’ sewer systems date back to this time period. These CSOs are concentrated around the New York and Philadelphia metropolitan areas, as shown below.

FIGURE 2: Map Displaying NJ CSO Sites - Most Are Located Close to New York City and Philadelphia (Image Source: NJ Department of Environmental Protection)

What is being done about CSOs?

Since the environmental movement in the 1970s, the federal government and state governments have been working together to deal with CSOs. The driving legislation behind dealing with CSOs has been the Clean Water Act. Under the Clean Water Act, waterway pollution regulations have been implemented, and point sources of pollution (i.e. Those that can be easily identified) have been required to have a permit.

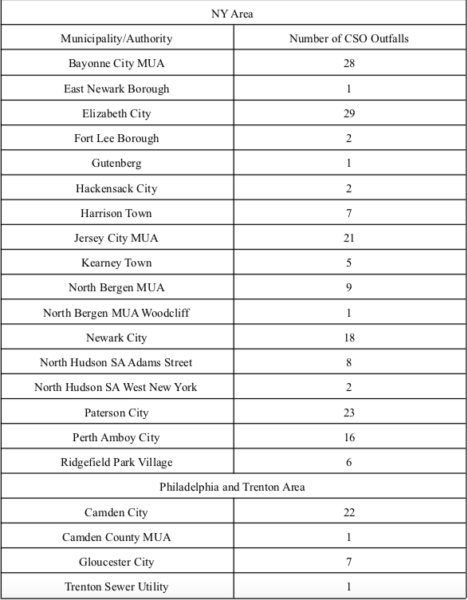

In order to meet Clean Water Act regulations and deal with CSOs, New Jersey has issued permits to municipalities with CSOs and required that they submit Long-Term Control Plans (LTCPs) as to how they will effectively deal with the CSO problem. A summary of which municipalities/authorities have permits and how many outfalls each permittee has in the table below.

TABLE 1: CSO Municipalities and Number of Outfalls (Data from NJ DEP)

The deadline for LTCP submittals was actually quite recent, in October 2020. As of now, several LTCPs are pending review from the NJ Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). Unfortunately, analysis of LTCPs shows that many municipalities with CSOs are doing too little, and the little that they will do will be achieved slowly.

Take the North Hudson Sewerage Authority - Adams Street and the Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission. Both organizations represent municipalities with significant numbers of CSOs that are responsible for much of the NY/NJ area’s CSO-related pollution. In their LTCPs, these organizations had an option to choose one out of three criteria put forth by the EPA to show that they are controlling CSOs effectively enough: have no more than an average of four events per year, collect no less than 85% of total sewage-stormwater volume, or eliminate “no less than the total mass of pollutants” responsible for impairing water quality. As can be expected, both organizations chose the “85%” requirement, as achieving the other two is quite ambitious. Unfortunately, this requirement still means that whatever plan is implemented will still have each organization releasing 15% of total stormwater-sewage volume, an amount that still results in billions of gallons a year. Thus, the problem is not truly being solved with this approach.

Additionally, the LTCPs are planning to achieve their progress quite slowly. The North Hudson Sewerage Authority plans to finish its improvements by 2048, while the Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission has its ending date as 2060. With this pace of improvement, it is unlikely that local water quality will improve anytime soon.

What can be done to change things?

CSOs cannot be eliminated overnight, but there are steps that can be taken to achieve more than what municipal LTCPs envision, both in scope and in speed. The key factor here is money. The North Hudson Sewerage Authority - Adams Street projects its improvements to cost a little over $300 million, while the Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission projects a price tag of $1.220 billion. Considering these large sums for achieving a partial success of 85% volume capture, it is no wonder that municipalities are choosing this criterion. Money is the key to achieving more and faster. Thus, the key to solving this problem is to increase funding for the NJ DEP, which would then be able to implement more programs to deal with CSOs.

Governor Murphy, in his fiscal year (FY) 2022 budget proposal, is proposing a $26 million increase in the DEP budget. However, this comes after years of budget cuts. In 2015, the NJ DEP budget was around $137 million. New Hampshire, a state with less than a sixth of New Jersey’s population, spent $188 million in the same year for environmental services. The money allocated to the DEP for FY 2022 will not be nearly enough to make substantial progress on CSOs.

Funding for the DEP should be achieved in two main ways. The first is through reallocation of the present funds available. This would result in less funding for other organizations and causes, but it would promote New Jersey’s environmental, recreational, and economic health in the years to come. For example, take property tax relief. The governor’s current budget earmarks payments to single parents making up to $75,000 annually and married couples making up to $150,000 to relieve their property taxes, payments which could amount to $500 per recipient. $500 times possibly 760,000 recipient families equals almost $40 million in payments, money that could go to the DEP. While this would eliminate property tax relief, programs to deal with CSOs would create jobs, thus possibly being even more helpful to NJ’s low-income communities.

The second way to fund the DEP is through implementing new taxes. While raising taxes is an action many are wary of, in this case it is necessary in order to provide a stable, sufficient source of revenue for the DEP. This will not bring in all needed revenue, but expanding on recent legislation taxing major producers of stormwater runoff would be a start. This would also incentivize organizations that produce runoff, such as large stores and malls, to implement strategies to reduce runoff and CSO severity, such as rain gardens and permeable pavement. Additional taxes, such as a carbon tax and maybe even raising the state gas tax to eliminate state withdrawal of the DEP budget for NJ Transit, could also help to get the job done.

Key Takeaways

CSOs have been part of New Jersey’s infrastructure for more than a century. In that time span, they have released billions of gallons of sewage into New Jersey waterways, hurting public health and recreational and economic prospects. Current plans to deal with CSOs will achieve too little in too much time. The key to dealing with CSOs effectively is to increase state funding for the DEP through the reallocation of state finances and the establishment of new taxes.

Sources:

- NY/NJ Baykeepers - Combined Sewer Overflows

- NJ DEP - What is a Combined Sewer Overflow?

- NJ DEP - Combined Sewer Overflow

- EPA - Clean Water Act Overview

- NJ DEP - CSO Permittee Info (CSO Municipalities, Number of Outfalls)

- NJ DEP - Long Term Control Plan Submittals

- North Hudson SA Adams Street LTCP

- North Hudson SA Adams Street LTCP Summary Slideshow

- Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission LTCP

- NJ Spotlight News Article - Main Points of FY 2022 Budget

- Insider NJ Article - Interview With Sierra Club Over Environmental Implications of FY 2022 Budget

- North Jersey News Article - Overview of Murphy Runoff Tax InitiativeBallotpedia - Environmental Spending Statewide (Data From 2015)